|

| Michael Jordan: Class of 1981 |

Updated Version: (02/17/13) MJ b4 MJ: 50th Birthday Edition

Written By: Inside Carolina Magazine

Today, Michael Jordan is an icon.

The former UNC All-American is widely recognized as the greatest player in NBA history, a gifted athlete who remains one of the most recognizable figures in sports even a decade after his playing days have ended.

Written By: Inside Carolina Magazine

The former UNC All-American is widely recognized as the greatest player in NBA history, a gifted athlete who remains one of the most recognizable figures in sports even a decade after his playing days have ended.

But in the early summer of 1980 "mike" Jordan was just another young basketball player-his promise discerned by just one ACC coaching staff...a secret that only Dean Smith and his loyal assistants had discovered.

North Carolina's current head coach can laugh about it now, since the story ended up happily-UNC, did in fact land Jordan and the gifted young prospect did help UNC claim the 1982 national tittle and three ACC regular season championships. Jordan left a legacy at UNC that abides today-current sophomore star Harrison Barnes cited his lifelong admiration of Jordan as one factor in his decision to sign with the Tar Heels.

Still, Williams mistake cost Smith and his staff some anxious moments and put the young assistant coach in an awkward position at the time. It's hard to fault Williams since it could be perceived that his "mistake" was in putting the interests of the kid he was recruiting ahead of the interests of the UNC program.

UNMILKED

Bob Gibbons, a young recruiting writer from Lenoir, N.C., was introduced to Jordan in the summer of 1979.

“Bobby Cremins was the coach at Appalachian State at the time and he had the Laney team up at his camp as a group,” Gibbons said. “I knew Bobby pretty well and he called me and said, ‘Bob there’s the kid up here you’re not going to believe.’”

“I saw a 6-3 player with explosive athletic ability,” Gibbons said. “But what impressed me was what Michael said when Bobby introduced him to me—‘Mr. Gibbons, what do I need to do better to be a better player?’ That sums up Michael Jordan … he was always trying to get better. Even in his last years in the NBA, he worked harder than the rookies.”

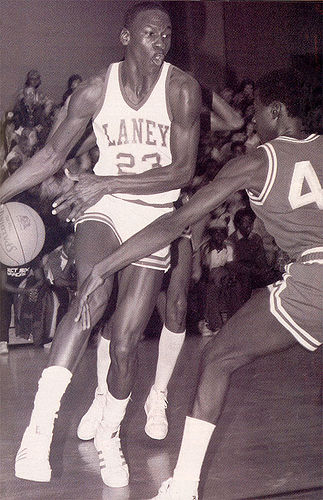

Jordan continued to fly under the radar, even though as a junior at Laney, he was a force—averaging over 25 points a game for a powerful 4-A (North Carolina’s highest classification) team.

Yet, somehow only North Carolina noticed—at least among the Big Four powers.

It helped that Bill Foster at Duke and Norm Sloan at N.C. State were in their final seasons and already had one foot out the door. Mike Krzyzewski (coach K's recruiting letter to MJ) and Jim Valvano—two coaches who would join the Jordan pursuit very late—were still at Army and Iona respectively when Bill Guthridge first saw Jordan play at Laney High.

Even so, recruiting in North Carolina had been a priority ever since Dean Smith replaced Frank McGuire as head coach in the summer of 1961. McGuire had preferred to build his team around his pipeline from the New York City area, but recruiting restrictions that Smith inherited—the result of the university’s de-emphasis on basketball after national point shaving scandals—forced Smith to rely heavily on homegrown talent to rebuild his program

Smith enjoyed considerable success with the likes of Fayetteville’s Rusty Clark and New Bern’s Bill Bunting, anchors of his first great team. He followed with Charlie Scott (a New Yorker who prepped at Laurinburg Institute), Charlotte’s Bobby Jones, Greensboro’s Bob McAdoo, Rocky Mount’s Phil Ford and Gastonia’s James Worthy. There were some misses too—losing Shelby’s David Thompson (Jordan's favorite player growing up) and Tommy Burleson of Avery County gave N.C. State a brief edge in the rivalry; losing Durham’s John Lucas and Rocky Mount’s Buck Williams to Maryland hurt in the 1970s.

|

| UNC staff that recruited Jordan: Williams, Fogler, Guthridge, Smith |

Guthridge made the trip to the North Carolina coast after receiving a tip from Mike Brown, the athletic director of the New Hanover County schools. When he returned from his first view of Jordan, Smith asked his trusted aide what he thought.

Guthridge reported that the kid had exceptional quickness and great hands. Then he added: “He’s unmilked.”

Writing in his autobiography in 1999, Smith explained that he took Guthridge’s words to mean that “while Michael had some obvious talents that couldn’t be coached, there was a lot to teach.”

“Roy told me I had to keep the tip secret because Coach Smith didn’t want the media people talking about him,” Oettinger recalled. “He told me ‘There’s this guy named Mike Jordan at Laney. Coach Guthridge has been to see him three times. He does 360 degree dunks like it’s nothing.’”

Oettinger checked the schedule and saw that Laney was playing a game at Southern Wayne High School—the defending state 4-A champion—and decided to check Jordan out himself.

“I went with three friends,” he said. “Laney won by 20 and was up 30 at one point. Jordan was just fabulous. I wrote in our next issue—February of 1980—that ‘You probably haven’t heard the name Mike Jordan, but he has the best combination of athleticism, basketball skills and intangibles of any high school wing guard that I’ve ever seen.’

“[Poop Sheet publisher Dennis Wuycik] used that quote in promotions for more than 20 years.”

OVERNIGHT SENSATION

“Very few people knew about him at that time,” Williams recalled. “Michael came and he just destroyed everybody in the camp.”

What impressed Smith and his staff was Jordan’s hunger to learn. He kept sneaking into drills. They couldn’t get him off the court. By the end of the session, the Tar Heel coach knew that he was sitting on a special prospect.

But he also knew that Jordan was about to go national.

In his autobiography, Smith explained that Williams and assistant coach Eddie Fogler had—without his knowledge or consent—called Howard Garfinkel, who ran the prestigious Five-Star Camp in Honesdale, Pa. (near Pittsburgh), and arranged for Jordan to attend.

That’s not quite what happened, according to Williams.

“One night during [UNC’s] camp, Pops told me that he had also got Michael an invitation to the Five-Star Camp or the BC camp,” Williams said.

Herring wanted Williams’s advice about attending one of the camps.

“He asked me what I thought,” Williams recounted. “I said, ‘I think he should go. I think it would be a great test of him. If I had my choice, I would go to the Five-Star Camp.’ I thought that would be better for him because it was such a good teaching camp. It wasn’t just about playing games. It was teaching the fundamentals of the game of basketball.

“So I called Howard Garfinkel and told him that Michael was coming and he would really be pleased with him as a player. I told Garf, ‘He’s going to be good enough to be a waiter.’ You see, if you could wait tables, you could go two weeks for the price of one. So I did call Garf and talked about the opportunity. “

Smith told Williams that it would have been better if Jordan did not attend Five-Star.

“I said, ‘Coach, in my opinion, he was going to go and I was just trying to give him some guidance about what I thought would be best for him,” Williams responded. “And Michael’s family really appreciated it.”

As it turned out, Smith’s worst fears were realized at Five-Star. Jordan enjoyed a spectacular double session. He was the MVP of the first session and the only reason he didn’t win the second-session MVP was that camp rules prevented one player from winning that award twice.

“He won seven awards in the two sessions,” Oettinger recalls.

Afterward, Garfinkel rated Jordan as one of the top 10 prospects in the class. Oettinger ranked him No. 2 behind Georgetown recruit Patrick Ewing. Gibbons rated Jordan No. 1—ahead of Ewing.

“I had gone to several of his games during his junior year and I was there at Five-Star,” Gibbons said. “You can’t believe how I was ripped for ranking Jordan ahead of Ewing—everybody said I was taking care of a hometown boy.”

But after the Five-Star Camp, plenty of coaches knew how good Jordan was.

Smith suddenly found himself recruiting against South Carolina, where ex-Duke coach Bill Foster took Jordan to meet the governor; N.C. State, where Valvano turned on the charm and encouraged Jordan to follow in the footsteps of his childhood hero, David Thompson; and Maryland, where Lefty Driesell tried to convince Jordan’s father that with the opening of the new Chesapeake Bay Bridge, College Park was as close to Wilmington as Chapel Hill.

In the end, Jordan elected to sign with UNC.

Gibbons doesn’t think that UNC’s Smith ever had anything to worry about. “I’m sure he did worry and I’m sure he had to work a little harder,” the veteran writer said. “But Michael and his family loved North Carolina.”

One of the reasons that the Jordans never wavered was Williams's “mistake”—they believed the young assistant was looking out for Michael’s interest.

“Michael’s Dad was always very appreciative,” Williams recalls.

Indeed, to show his appreciation, Jordan’s father hand-built a wood-burning stove for the young assistant coach. He would build Williams a new stove for every house he moved into.

THE LEGACY

It didn’t help that he signed the same day as Lynwood Robinson, a point guard from Southern Wayne High School and the MVP of the previous year’s 4-A state tournament. UNC’s Fogler had described Robinson as “the next Phil Ford” and his commitment stole the headlines from Jordan—except in Durham, where sports writer Keith Drum, who had been at Honesdale and seen Jordan dominate the nation’s best prospects, told anybody that would listen that Jordan was by far the more important signee.

It’s interesting to note that Drum later left journalism and has spent the last two decades as an NBA scout.

Jordan was also the victim of some curious omissions that confused a public that was not as recruiting-savvy as today's fans.

For instance, Street and Smith’s Yearbook —at the time the only important preseason publication in college basketball—usually listed 650 high school seniors as top prospects. But the 1981 edition didn’t include Jordan—editor Dave Krider later wrote that his North Carolina contact didn’t include Jordan among the top 20 juniors in North Carolina.

After the 1980-81 season, the Associated Press poll picked Asheville’s Buzz Peterson over Jordan as the state’s prep player of the year. Peterson, who later roomed with Jordan and became one of his best friends, was always embarrassed by the vote.

Then there was the 1981 McDonald’s All-American game, held in Wichita, Kansas. Jordan scored a record 30 points, including the tying and game-winning free throws with 11 seconds left as the East edged the West 96-95. He hit 13-of-19 field goals, 4-of-4 free throws and added six steals and four assists.

Somehow, the MVP vote was split between Adrian Branch and local favorite Aubrey Sherrod.

Over the years, the myth has grown that Jordan was a late-bloomer (well, he was cut from his high school team before his sophomore season) or that he was an unknown when he arrived at UNC (he was not). It’s understandable that with all the odd twists and turns in his path from unknown to superstar that some confusion would arise.

But it’s really very simple—entering the summer of 1980, Mike Jordan was largely unknown to the public and to the majority of the basketball community; by the end of that summer, he remained a mystery to the public, but was widely recognized within the basketball community as one of the nation’s great prospects.

By the time Michael Jordan ended his freshman season at UNC, he belonged to the world. Click for Original Article.

No comments:

Post a Comment